Stepping Back in Time: Exploring the Historical Public Bath of Ali Qoli Agha in Isfahan

Ali Gholi Agha Hammam

For centuries in Persian culture, cleanliness extended beyond mere hygiene, deeply intertwining with social customs and even religious practices. Establishing a public bath, or hammam , was considered a benevolent act within the community. Following the Arab and Mongol invasions, the public bath became a crucial congregational space, offering respite for both dissenters and everyday individuals. More than just a place to cleanse the body of dirt and improve health, the public bath served as a social hub for massages, grooming by barbers, and even informal discussions on various matters. Barbers also attended to basic hygienic needs, including hair trimming and, according to early Islamic customs, rudimentary dental work and circumcisions. The public bath held ceremonial significance, hosting joyous occasions like post-childbirth rituals and pre-wedding ceremonies for brides and grooms separately. It was also a place for purification after religious rites, such as washing after burial ceremonies. Islamic tenets further emphasized cleanliness, mandating ritual washing after touching a deceased body and encouraging purification before attending Friday prayers at the Jami mosque. Women were also required to cleanse themselves after menstruation and during pregnancy. Given Iran's arid climate and the scarcity of water, private baths were a rarity, even for the affluent, making the public bath the essential and often sole option for personal hygiene. Consequently, public bath facilities in larger cities evolved into sophisticated and intricate systems, with the historical public bath of Ali Qoli Agha in Isfahan standing as a prime example of this cultural and architectural concept.

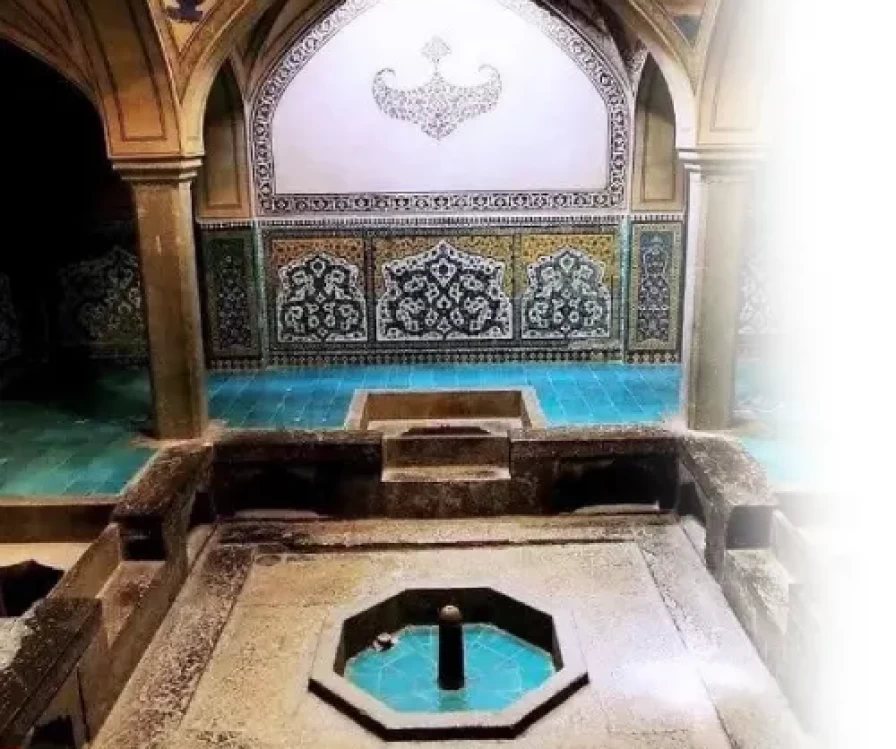

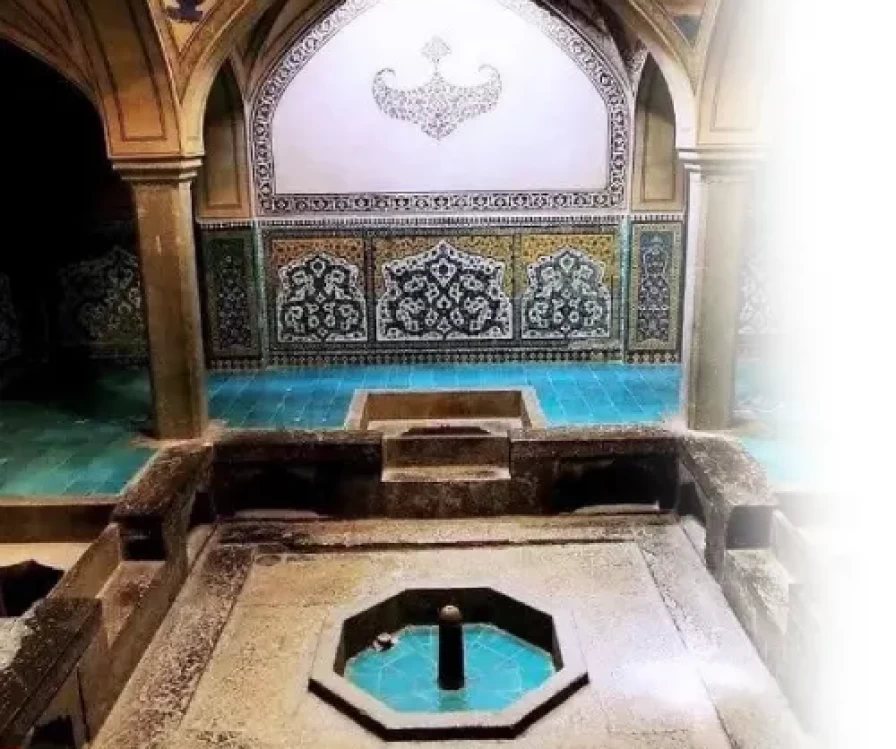

The historical public bath of Ali Qoli Agha , like most public baths throughout Iran, adhered to a general structural blueprint, adapted to the size and location of the city or town. Usage customs remained largely consistent, with minor regional variations. Larger urban centers, such as Isfahan, sometimes featured twin, back-to-back bathhouses to accommodate separate services for men and women during daylight hours. In smaller, local public baths, a single space often served women from early morning until around noon or twilight, and men from noon until evening and early night, primarily for security reasons, while maintaining the same underlying structure. The Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath exemplifies the latter, comprising two spacious halls for washing and a hot pool situated at the end.

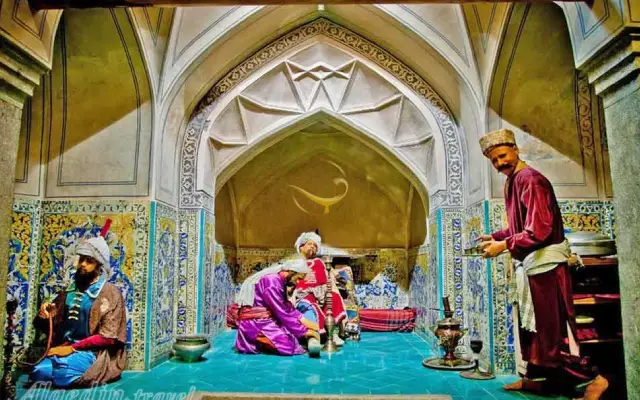

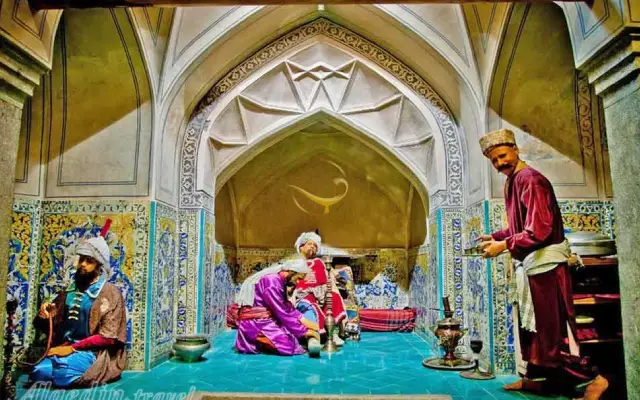

Entering a public bath, such as the historical public bath of Ali Qoli Agha , involved passing through an entrance chamber called "sarbineh." This transitional space was ingeniously designed to moderate the temperature difference between the interior, which was considerably hot, and the exterior, particularly crucial during the cold winter months. Upon entering the sarbineh, patrons would remove their clothing and place their shoes in designated cubbyholes for safekeeping. Men and women would then wrap their lower and upper bodies with two pieces of cloth known as "Long," a practice still visible today with red-colored fabrics available in many Iranian shops. They would pause in the sarbineh to allow their bodies to acclimatize to the warmer temperature inside. Subsequently, the bath's owner or attendant would guide them further. A small cold-water pool was typically located in the center of the first washing area. After washing, patrons would request a dry cloth from the attendant, who would provide two pieces, akin to towels. Before fully exiting the washing area, individuals would often dip their feet in cold water to gradually lower their body temperature and would linger there as needed. Patrons who paid a higher fee could access enhanced services, with wealthier individuals sometimes opting for massages and cold beverages like sherbet, tea, or fruit juice in a designated relaxation area. Following this, they would take time to cool down, don their clean attire, pay the fee, and depart the bath.

Most public baths, including the Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath , were community-owned, often established and endowed to the public through charitable donations known as "vaqf." Wealthy families, businessmen, or influential figures like Ali Qoli Agha, who enjoyed favorable relations with the Safavid government and possessed substantial wealth, would often donate these significant structures. In return, those who used the bath would offer prayers for the donor and their family, seeking blessings for them in the afterlife. The donated funds and subsequent contributions from other affluent individuals were used to maintain the bath, purchase fuel for heating the pools, and pay the staff. A strict management system ensured continuous service, operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, throughout the year. The manager, known as "ostad" (master), oversaw all aspects of the bath, from hygiene standards to regulating access to services.

Strict protocols were in place to ensure the cleanliness and safety of the public bath, with efforts made to keep individuals with contagious illnesses away. The management of ill patrons depended on the size of the bathhouse and the methods for controlling the spread of diseases. If an illness was detected, the affected person would be quarantined and washed in a separate, smaller area during the very early morning or late evening to minimize contact with others. Simultaneously, local physicians would be consulted for treatment. By managing illnesses effectively, they aimed to prevent epidemics within the community. Inside the main bathing areas, specific hygienic rules were mandatory and strictly enforced.

The Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath featured two primary spaces for washing and a dedicated, more elaborate section for wealthier patrons who paid extra for enhanced service. This exclusive area, often called "shah neshin" (king's seat), was typically adorned with precious stones like white and green marble. Beyond the washing areas were three adjacent pools: one filled with cold water, another with lukewarm water, and the largest containing very hot, near-boiling water, resembling a modern-day jacuzzi. Patrons would never enter the hot pool without first cleansing themselves by pouring water from a pitcher called "Doolche" or "Dalvche." This act of purification, known as "Ghosl," holds significant importance with defined rules in Islamic Sharia.

Given Iran's arid climate and the high cost of water, even a single drop was valued. Wood and other common burning materials were scarce, limited to desert shrubs and scattered bushes. Consequently, bathhouses burned any available fuel in a furnace called "Tiun," managed by a worker named "Tuntab," a physically demanding job. The "Tuntab" lived near the furnace, his face perpetually stained with soot and ash, working tirelessly through scorching summers and freezing winters. Others were tasked with gathering and transporting fuel year-round. Heat from the fire was ingeniously transferred to the pools using a large copper bowl situated at the bottom. The bowl was sealed against the water, with the fire burning underneath in an open fireplace. The insulation system, though a closely guarded secret, typically involved mortars to ensure its integrity. Isfahan was renowned for its skilled coppersmiths who crafted these specialized copper bowls to prevent leaks, while the furnace workers carefully regulated the fire to maintain optimal water temperature without damaging the copper. This ingenious heat exchange system was widely adopted throughout the country. The Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath still allows visitors to observe this system today. The ceiling of the bathhouse featured numerous holes covered by a unique lighting system called "JAAM," using glass lenses to allow natural light to illuminate the interior. Next time you visit Isfahan, be sure to experience the Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath . Join Sanapersian tour and travel service provider group in Isfahan to see the Ali Qoli Agha historical public bath .

Contact Us

+989054577261